Maritime Attorney Ryan Melogy Worked With 2 CNN Reporters to Expose the Coast Guard’s Operation Fouled Anchor Scandal. It took Years of Work & This is How They Did It.

Summary

This comprehensive investigation was written by Bartram Lewis and is based on years of legal advocacy, FOIA litigation, and survivor reporting led by maritime attorney Ryan Melogy, with investigative reporting by CNN journalists Blake Ellis, Melanie Hicken, Audrey Ash, Curt Devine, and Pamela Brown. Lewis explains a little-known back story about how the U.S. Coast Guard’s Operation Fouled Anchor sexual-assault cover-up was exposed, and why it took years of sustained legal advocacy, investigative reporting, and survivor courage for the truth to come out.

While the public first learned of Operation Fouled Anchor through CNN’s June 30, 2023 reporting, the events that made that disclosure possible began years earlier. Long before the Fouled Anchor investigation was leaked by a still-anonymous Coast Gaurd insider, maritime attorney Ryan Melogy was documenting patterns of sexual abuse at sea, uncovering the Coast Guard’s failure to enforce reporting laws, litigating Freedom of Information Act cases, and publishing evidence that the agency systematically concealed sexual misconduct by credentialed mariners and academy officials.

The story traces the origins of the scandal back to Melogy’s own experiences aboard Maersk and Crowley commercial vessels beginning in 2014, including his reporting of shipboard sexual abuse, the retaliation he alleges followed, and his discovery that the Coast Guard had quietly refused for decades to enforce the federal shipboard sexual-assault reporting law, 46 U.S.C. § 10104. That discovery became the foundation for a broader investigation into how the Coast Guard handled—or failed to handle—sexual violence across the maritime industry.

In 2020, Melogy launched Maritime Legal Aid & Advocacy and began publishing survivor accounts and internal Coast Guard records obtained through FOIA litigation. These disclosures revealed a hidden system of secret settlements, minimal punishments, and deliberate efforts to keep sexual-misconduct cases out of public view and away from Congress. That work forced the Coast Guard to bring its first public sexual-misconduct credential case in decades, a case in which Ryan Melogy served as the Coast Guard prosecutors’ star witness, and a case that laid the groundwork for intense congressional scrutiny of the Coast Guard’s Suspension & Revocation program.

The article then follows the pivotal moment in 2021 when a U.S. Merchant Marine Academy cadet—known publicly as “Midshipman-X”—came forward through Melogy’s platform, triggering national media attention and drawing CNN reporters Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken into the investigation (Melogy would eventually represent Hicks in a historic civil lawsuit against shipping giant Maersk that again rocked the maritime industry, securing a resolution to her civil case in November of 2022).

Beginning in September of 2021 when Hicks first blew the whistle via Melogy’s platform, and continuing for the next two years, Ellis and Hicken reported extensively on sexual abuses at sea, failures at the Merchant Marine Academy, and the Coast Guard’s systemic unwillingness to police sexual violence in the maritime domain.That sustained reporting, combined with Melogy’s FOIA litigation and survivor advocacy, directly influenced Congress’s passage of the Safer Seas Act in 2022, which fundamentally changed maritime law and culture by strengthening shipboard harassment and abuse reporting requirements, mandating permanent credential revocation for sexual assault at sea, and mandating the installation of security cameras to monitor crew stateroom doors aboard American commercial vessels.

The article culminates with the exposure of Operation Fouled Anchor itself—a secret Coast Guard investigation into decades of sexual assaults at the Coast Guard Academy that senior leadership concealed from Congress and the public. It also examines what happened after the scandal broke, including the 2024 whistleblower revelations of Shannon Norenberg, the Coast Guard Academy’s longtime Sexual Assault Response Coordinator, who, while being represented by whistleblower attorney Ryan Melogy, disclosed that she had been unknowingly used as part of the cover-up and directed to mislead survivors and discourage them from speaking to Congress.

Norenberg’s decision to come forward—coordinated with CNN reporting and timed ahead of Senate testimony by Coast Guard leadership—confirmed that Operation Fouled Anchor was not merely a failure of the past, but a living system of concealment that extended into the present. Her account provided a rare insider view of how the cover-up functioned operationally and why it remained hidden for so long.

Ultimately, this is not just the story of a leak or a single investigation. It is the story of how institutional silence was dismantled—piece by piece—through persistence, documentation, survivor trust, whistleblower courage, and investigative journalism—and how one legal fight inside the maritime industry grew into a national reckoning for the United States Coast Guard.

January 9, 2026

By Bartram Lewis

After CNN reporters Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken broke the U.S. Coast Guard’s Operation Fouled Anchor (OFA) scandal on June 30, 2023, Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut pulled no punches when he called the calculated coverup by the most senior leaders of the United States Coast Guard, “probably the most shameful, disgraceful incident of cover-up of sexual assault that I have seen in the United States military–ever.”

As Chairman of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs’ Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Senator Blumenthal held the first Congressional hearing into the Operation Fouled Anchor coverup on December 12, 2023. The televised, emotional “Coast Guard Academy Whistleblowers: Stories of Sexual Assault and Harassment” hearing was held in the Dirksen Senate Office Building–nearly 6 months after CNN broke the OFA scandal.

CNN’s Hicken and Ellis were present at the December 12, 2023 hearing, and subsequently wrote the testimony they witnessed from Coast Guard Academy survivors was, “at times highly critical of the agency and at others deeply emotional,” and “prompted senators on both sides of the political aisle to lambast current and former Coast Guard leaders.” According to Hicken and Ellis, the four whistleblowers who testified at the hearing told Senators, “they were subjected to sexual assault and harassment at the US Coast Guard Academy” and “they were silenced, retaliated against and left battling severe mental trauma while alleged perpetrators continued to thrive within the service.”

Senator Blumenthal pledged to those watching the hearing that his ongoing investigation of the Operation Fouled Anchor coverup would expose “a culture of cover-up that the Coast Guard has spawned and sustained for decades” whereby the agency “has discouraged and deterred victims and survivors of sexual abuse at the Coast Guard Academy from coming forward…denied them justice, and…failed to protect them from retaliation and reprisal when they have stood up and spoken out.”

By early 2024, many important questions about Operation Fouled Anchor and its subsequent coverup by Coast Guard leaders remain unanswered, but what seems certain is that this unfolding scandal and its fallout are far from over. In addition to the ongoing Senate investigation of OFA, on December 8, 2023 the Republican-led House Committee on Oversight and Accountability opened a probe into the OFA coverup, as well as a broader investigation “into the U.S. Coast Guard’s mishandling of serious misconduct, including racism, hazing, discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape, and the withholding of internal investigations into these offenses from Congress and the public.”

One of the important questions being asked by the Congressional Committees investigating the Fouled Anchor scandal and by people who have been following the shocking revelations of over-the-top corruption at the highest levels of the Coast Guard is, “how did the existence of the Fouled Anchor coverup ever come to light in the first place?”

There exists a general awareness that the Fouled Anchor scandal was broken by CNN, but there is less public awareness that CNN reporters Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken worked tirelessly for nearly two years on stories related to the U.S. Coast Guard and its policies towards sexual harassment and assault before they exposed the Fouled Anchor scandal, or that the investigative efforts that led to breaking the Fouled Anchor coverup began several years before the involvement of Ellis and Hicken.

The story of how the U.S. Coast Guard’s coverup of Operation Fouled Anchor was “uncovered” began with Ryan Melogy, a maritime attorney and activist who began investigating the U.S. Coast Guard’s handling of sexual assault and harassment cases in 2019—four years before the coverup of Operation Fouled Anchor was exposed by Hicken and Ellis of CNN on June 30, 2023.

“An Epic Sexual Assault Scandal 30 Years in the Making”

The U.S. Coast Guard is the primary law enforcement agency responsible for the entire maritime domain of the United States, and the agency is responsible for investigating crimes committed aboard American-flag vessels upon the high seas. In 2019 Melogy began investigating the Coast Guard’s record of enforcing laws against shipboard sexual abuse in the U.S. maritime industry while involved as a witness and victim in what would become one of the most publicized sexual assault cases in the history of the Coast Guard.

After more than a year of investigation into Coast Guard policies and practices that he says “frustrated and horrified me,” Melogy started the non-profit legal advocacy organization Maritime Legal Aid & Advocacy (MLAA) in June of 2020 with the stated purpose of exposing the U.S. Coast Guard’s “intentional failures to protect American merchant mariners from harassment and sexual abuse aboard American vessels at sea.”

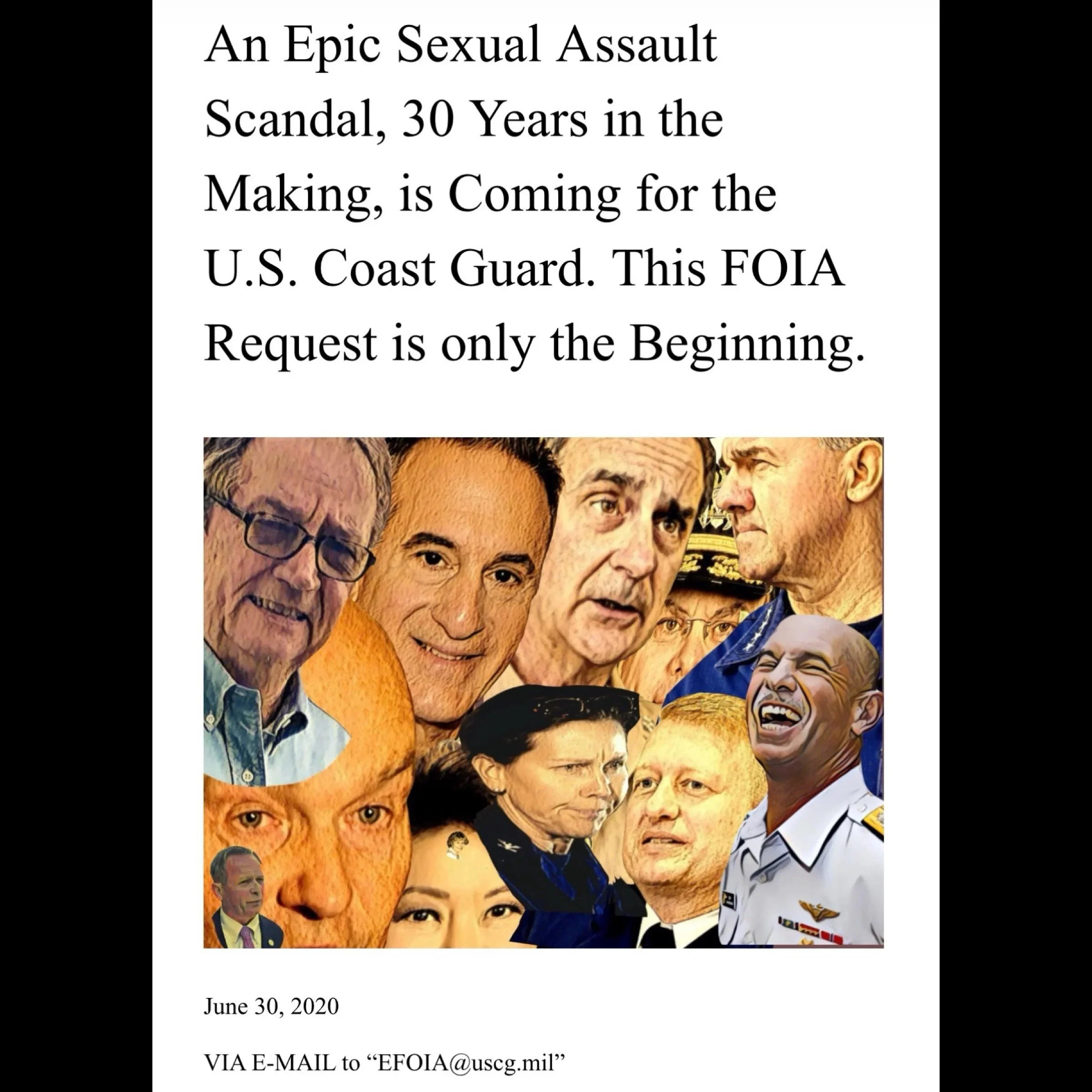

On June 30, 2020 Melogy published MLAA’s first blog post titled, “An Epic Sexual Assault Scandal, 30 Years in the Making, is Coming for the U.S. Coast Guard. This FOIA Request is Only the Beginning.” The blog post was also a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request submitted to the U.S. Coast Guard by Melogy and MLAA that would later turn into a FOIA lawsuit against the Coast Guard when the Coast Guard refused to turn over the requested records related to its record of investigating and punishing maritime sex crimes.

The artwork that accompanied MLAA’s first blog, which predicted the emergence of an epic scandal that would engulf the U.S. Coast Guard, featured a collage of faces of government officials, including the faces of then-Coast Guard Commandant Karl Schultz and then Vice Commandant Charles Ray.

Few inside or outside of the Coast Guard took Melogy or MLAA seriously at the time, but three years later the prediction made by Melogy in the June 30, 2020 blog post would come true. On June 30, 2023—exactly 3 years to-the-day after Melogy published the Epic Sexual Assault Scandal blog post on MLAA—CNN reporters Ellis and Hicken published their bombshell story that broke the Fouled Anchor scandal.

In their June 30, 2023 story for CNN, Ellis and Hicken wrote:

“A secret investigation into alleged sexual abuse at the US Coast Guard Academy, the training ground for the Coast Guard’s top officers, uncovered a dark history of rapes, assaults and other serious misconduct being ignored and, at times, covered up by high-ranking officials. The findings of the probe, dubbed “Operation Fouled Anchor,” were kept confidential by the agency’s top leadership for several years. Coast Guard officials briefed members of Congress this month after inquiries from CNN, which had reviewed internal documents from the probe.”

What has ensued since Ellis and Hicken’s broke their June 30, 2023 bombshell story on Operation Fouled Anchor can be accurately characterized as an Epic Coast Guard Sexual Assault Scandal [at least] 30 years in the Making. But how did a FOIA Request slash Blog Post (on a brand new Squarespace blog) about the Coast Guard’s longstanding policy of ignoring and covering-up widespread sexual abuse in the U.S. maritime industry eventually lead to exposing the infamous Fouled Anchor scandal? The answer is long, winding, and wild.

The M/V Maersk Idaho

It all began in late November of 2014 aboard a container ship called the M/V Maersk Idaho, owned and operated by Danish shipping giant Maersk. Around Thanksgiving of 2014 Melogy walked up the gangway of the M/V Maersk Idaho in Port Elizabeth, New Jersey and became the vessel’s 2nd Mate. A graduate of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and the University of Virginia School of Law, Melogy was already a legally trained person when he joined the Maersk Idaho in 2014.

When Melogy joined the M/V Maersk Idaho, what would become the sprawling Operation Fouled Anchor investigation was just getting underway within the Coast Guard. According to the Fouled Anchor Final Report, OFA arose “out of an investigation the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS) opened in September 2014 after an officer disclosed she was raped while at the Coast Guard Academy (CGA) 17 years earlier.”

When he joined the Maersk Idaho in November 2014, Melogy of course had no idea that what would become a sprawling CGIS investigation into Coast Guard Academy sexual assaults had been recently initiated within the Coast Guard, or that nearly a decade later he would play a key role in exposing the existence of the investigation and subsequent coverup.

Melogy would spend 70 days aboard the Maersk Idaho as 2nd Mate, sailing to Sri Lanka and the Persian Gulf before eventually departing the vessel in Genoa, Italy. Before he departed the vessel in February of 2015, Melogy delivered a Report to Maersk and to Captain Paul Willers, the master of the vessel, in which he accused Captain Mark Stinziano (then serving as the vessel’s Chief Mate) of sexually harassing him and also groping him during the voyage.

Melogy’s Report against Stinziano also included allegations of criminal sexual assaults against himself and two cadets from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy who were also serving aboard the Maersk Idaho with Melogy. According to Melogy, after he signed-off the Maersk Idaho in February of 2015, Maersk subsequently used the Idaho’s senior officers and their inhouse lawyers to conduct a coverup of his allegations against Stinziano, which included using senior Maersk officers aboard the vessel to intimidate at least one of the cadets into signing a statement denying Stinziano had engaged in sexual misconduct during the voyage.

Melogy would eventually file a detailed labor complaint against Maersk (Melogy vs. Maersk) that chronicled his time aboard the Maersk Idaho as well as the experience of coming forward to again report the allegations to the U.S. Coast Guard after Maersk and Captain Willers failed to notify the agency of Melogy’s Report themselves in accordance with 46 USC 10104.

About 9 months after he departed the Maersk Idaho, Melogy joined the M/V Washington Express as 3rd Mate. According to Melogy, aboard the M/V Washington Express he was subjected to retaliatory physical violence and psychological abuse that he claims constituted torture by Captain Karl Fidler, the master of the M/V Washington Express. Melogy claimed the abuse he endured aboard the M/V Washington Express was retaliation for having “snitched” on a “union brother” by reporting Stinziano’s shipboard sexual abuse to Maersk in Febuary of 2015. Fidler and Stinziano were both senior members of the International Organization of Masters, Mates, & Pilots (MMP) maritime labor union.

The Washington Express was owned by German shipping giant Hapag-Lloyd AG, but the vessel was managed by U.S. based Crowley Maritime. Melogy would later file a harrowing labor complaint against Crowley Maritime Corporation (Melogy vs. Crowley) over the retaliatory shipboard abuse he says he endured aboard the M/V Washington Express in late 2015 and early 2016.

In his labor complaint, Melogy also alleged that the leadership of the International Organization of Masters, Mates, & Pilots (MMP) labor union were complicit in the retaliatory abuse he allegedly endured aboard the M/V Washington Express.

In June of 2019 Melogy publicly released his labor complaint against Maersk. The public release of that document would eventually set off an unprecedented and highly controversial investigation and prosecution of Captain Stinziano within the U.S. Coast Guard’s Suspension & Revocation Administrative Law Court.

As of February 2024—9 years after Melogy submitted his report to Maersk—the now-infamous case of USCG vs. Stinziano is still winding its way through the Coast Guard’s legal system. To the maritime community and to Congress, Stinziano has become a symbol of the Coast Guard’s failures to properly address the issue of sexual misconduct, and of the agency’s top-down willingness to tolerate, excuse, and downplay the seriousness of the crime of sexual assault. As the case continues to wind through the Coast Guard’s broken legal system, Captain Stinziano continues to sail aboard American merchant vessels under the authority of his Coast Guard-issued merchant mariner’s license, and he continues to supervise USMMA cadets at sea.

Despite coming to symbolize the Coast Guard’s shameful moral failures on the issue of sexual assault, within the U.S. Coast Guard the case of USCG vs. Stinziano is also recognized as the case that changed everything about how the Coast Guard handles merchant mariner sexual misconduct cases, as well as the case that eventually led to the exposing of the Coast Guard’s Operation Fouled Anchor coverup.

46 USC 10104

According to Melogy, following his experiences aboard the M/V Washington Express in late 2015 and early 2016 he began to experience severe PTSD symptoms due to the intense trauma that stemmed from the abuse he endured during horrific back-to-back shipboard experiences. Melogy says he began thinking about potential ways to fight back against what he had endured and ways to hold his abusers and their enablers accountable, but there were no obvious options available to him.

A few months after he departed the M/V Washington Express, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) announced “Sea Year” for Cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy was being indefinitely suspended. The June 16, 2016 announcement of a “Sea Year Stand Down” rocked the U.S. maritime industry and sparked angry protests against not only the Sea Year program’s suspension, but also angry denunciations against the very idea that the maritime industry had an abuse problem.

Two months after DOT and MARAD announced the Sea Year Stand Down, Donald Marcus, the long-time President of the International Organization of Masters, Mates, & Pilots labor union, along with the leaders of other prominent maritime labor unions, wrote a now-infamous letter to the U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx titled “MARAD Sexual Assault Response Strategy ‘Dangerously Off Course.’”

In his angry letter denouncing efforts by MARAD to combat the federal crime of sexual assault affecting students at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy during their “Sea Year” training aboard U.S. flag commercial vessels, Marcus wrote that he was “offended by the illogical, indefensible notion that inappropriate, even unlawful sexual behavior is rampant in the commercial U.S. merchant fleet.”

Marcus said the notion that sexual harassment and sexual assault were significant industry problems was “a class action affront to all American merchant mariners, regardless of where they work.” According to Marcus, unlike land-based office jobs where few doubted that sexual harassment and sexual misconduct were significant problems, life at sea was different.

In his 2016 letter Marcus wrote: “One principal fact of life at sea in the U.S. merchant fleet in all trades is that, unlike people with jobs ashore, American merchant mariners live where they work for months at a time. They tend quickly to see each other as family, and their day-to-day personal behavior typically reflects family values at their strongest.” Donald Marcus was also the man Melogy had accused of complicity in the retaliatory shipboard abuse he endured aboard the M/V Washington Express in 2015 and 2016.

During the 1st USMMA Sea Year Stand Down, which lastest from June 2016 through February 2017, leaders of the entire U.S. maritime industry were involved in policy discussions about sexual harassment and assault at sea aboard U.S.-flag vessels. The dynamic was generally one where industry forces expended great energy fighting back against the notion that the maritime industry had a significant problem with shipboard sexual misconduct. Groups of prominent female industry leaders even organized to promote their message that the maritime industry did not in fact have a sexual harassment and abuse problem.

Throughout the course of this public, industry-wide debate over sexual abuse at sea, the United States Coast Guard never seems to have said a word about the problem publicly. After extensive research, the writer has been unable to find any mention of the U.S. Coast Guard in relation to the 2016-2017 debates over the problem of maritime sexual abuse. Not even the USDOT or MARAD, which had asserted there was a problem, ever publicly asserted that the law enforcement agency with primary responsibility for the entire U.S. maritime domain had a role to play in solving a maritime crime problem.

After 8 months of what appeared to outsiders like bitter conflict with the maritime industry, the USDOT resumed sending USMMA cadets out to sea aboard commercial American-flag vessels in February of 2017, citing significant safety improvements. Melogy says he followed the USDOT’s Sea Year Stand Down closely, and that he strongly supported it because he had experienced first hand how the system protected sexual predators even when they were reported. But when he went to work on an American-flag car carrier in 2017, he says he found that none of the safety measures the USDOT touted to Congress were actually being implemented aboard the vessel.

The question of what Maersk had done with his Report against Stinziano, and the fact that Stinziano posed an active threat to USMMA cadets and junior crew members, continued to gnaw at Melogy, he says. Around the summer of 2018 Melogy says he learned Maersk had promoted Captain Mark Stinziano from Chief Mate to Captain. According to Melogy, this development alarmed him. Not only had Maersk not fired Stinziano following Melogy’s report about Stinziano’s allegedly abusive and criminal shipboard behavior, the company had actually promoted him to Captain. In his labor complaint against Maersk, Melogy wrote:

“When I learned that Stinziano was now the Master of a ship, I became extremely concerned for the safety of those Cadets, junior officers, and crew members who would be forced to serve under his tremendous authority, and I became angry at Maersk for promoting into a position of such immense power over the lives of his crew a man I had warned them about.”

In the summer of 2018, around the same time Melogy learned Maersk had promoted Stinziano to Captain, Melogy was also studying for the U.S. Coast Guard’s Chief Mate/Master merchant mariner license exam. While studying, Melogy came across an exam question—one of over 20,000 in the Coast Guard’s license question bank—that asked a simple question Melogy says he found “mind-blowing.”

The Coast Guard question asked, “What is the penalty for a vessel’s master who fails to notify the Coast Guard of an allegation of shipboard sexual assault in accordance with 46 USC 10104?”

In his more than 15 years in the maritime industry, Melogy had never heard of 46 USC 10104, or its reporting obligation. The answer to the exam question in front of him was even more shocking, he says. According to the USCG’s question bank and the U.S. Code, the maximum penalty for not reporting an allegation of shipboard sexual assault to the Coast Guard was only a $5,000 civil fine.

“Why hasn’t anyone ever heard of this law?” Melogy says he asked himself after conducting numerous empty internet searches and asking other mariners about their own awareness of 10104’s reporting requirements. Melogy knew that mariners had gone to jail for not reporting oil spills and pollution. But if you didn’t report a sexual assault or rape allegation you were only on the hook for a maximum $5,000 fine? To Melogy, that seemed “like madness.”

Through his own research, Melogy would learn that the shipboard sexual assault reporting requirements of 10104 had become part of the U.S. Code in 1990 following a 10 year battle by Anne Mosness and the Women’s Maritime Association (WMA) to have the reporting law created. The WMA wanted to protect female seafarers from sexual abuse, but following the enactment of 10104 in 1990, the U.S. Coast Guard, which strongly opposed the law because the agency did not want to investigate sexual abuse in the maritime industry, refused to enforce the new statutory reporting requirement, and refused to even notify the industry of the reporting requirement’s existence.

Melogy recognized that 46 USC 10104 applied to the written report about Stinziano that he had given to Maersk back in February of 2015. As Melogy understood the plain meaning of the statute, the reporting requirement of 10104 applied to both the master of the Maersk Idaho and Maersk, because Melogy’s written report alleged that Stinziano had committed at least 4 separate criminal sexual assaults aboard the Maersk Idaho, which Melogy had either experienced or witnessed.

To Melogy, there were only two possibilities regarding Maersk’s compliance with the reporting requirement of Melogy’s report under 46 USC 10104. One possibility was that Captain Paul Willers (the master of the Idaho) and/or Maersk had followed the reporting requirement of 46 USC 10104 and notified the U.S. Coast Guard that allegations of sexual assault had been made against Stinziano aboard their vessel. The other possibility was that neither Willers nor Maersk had complied with the law after receiving Melogy’s report, and had engaged in an illegal coverup.

After departing the Maersk Idaho, Melogy had never been contacted by the U.S. Coast Guard about his Report, and he strongly suspected that Maersk and Captain Willers had never notified the Coast Guard. That hunch turned out to be correct. In a letter sent to Maersk CEO William Woodhour by Rear Admiral Richard Timme on March 2, 2021, RADM Timme wrote:

…Although [Maersk] proceeded to conduct an internal investigation at the time, neither the master of the MAERSK IDAHO nor [Maersk] notified the Department of Homeland Security or the U.S. Coast Guard about the complaint of a sexual offense, as required by 46 U.S.C. § 10104. In early 2019, U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA) alumnus J. Ryan Melogy notified the Coast Guard of the allegations against Mr. Stinziano via email. The Coast Guard subsequently conducted a criminal investigation that uncovered evidence corroborating Mr. Melogy's 2015 allegations that Mr. Stinziano initiated unwanted sexual contact with two individuals and engaged in other unprofessional conduct that violated company policy while serving as Chief Mate on the MAERSK IDAHO.

Timme’s letter to Maersk CEO Woodhour had been prompted by a December 22, 2020 letter Maersk CEO Woodhour sent to Maritime Administrator Mark Buzby and Coast Guard Commandant Karl Schultz in which Woodhour complained that Maersk was being treated unfairly by the U.S. government regarding the ongoing investigation of Captain Mark Stinziano.

Maersk and Woodhour would eventually accuse the U.S. Coast Guard of engaging in a “systematic harassment” campaign against the company over 3 subpoenas issued to the Company by the Coast Guard related to Melogy’s report. Maersk would also file a lawsuit against the Coast Guard related to Melogy’s report, although the company would withdraw the lawsuit shortly after filing it when the company began to receive negative press attention for the tactics it was using against Melogy and the U.S. Coast Guard in its efforts to defend Mark Stinziano, whom Maersk had promoted to Captain and was still employing aboard its ships despite the ongoing criminal and S&R sexual abuse investigations against Stinziano.

In 2021, Maersk admitted it had not reported Melogy’s written 2015 allegations to the Coast Guard, and the company was issued an inflation-adjusted $10,000 fine, which was eventually reversed on appeal after Maersk engaged in what may have been an unprecedented all-out legal assault on the Coast Guard’s backwater Hearing Office.

Melogy would later prove, through FOIA requests and a lawsuit against the Coast Guard, that the $10,000 fine issued by the Coast Guard against Maersk for not reporting Melogy’s February 2015 allegations to the Coast Guard IAW 46 USC 10104 was the first and only fine for a violation of 10104 the Coast Guard had ever issued in the 30+ years the law had been part of the U.S. Code.

The Coast Guard’s retraction of its $10,000 fine against Maersk, its refusal to charge Captain Wilers with violating 10104, and Melogy’s outspoken activism regarding the failures of the U.S. Coast Guardto enforce the reporting requirement of 46 USC 10104 would eventually cause Congress to revisit the law for the first time in more than 30 years.

Melogy’s policy paper titled “The Long, Tragic History of 46 USC 10104, AKA ‘The Federal Shipboard Sexual Assault Allegation Reporting Law’” circulated widely on Capitol Hill and would become the basis for a dramatic and historic strengthening of the reporting requirements of 46 USC 10104 that were included in historic maritime legislation called the “Safer Seas Act,” which was passed by Congress in December of 2022 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) and subsequently signed into law by President Joe Biden.

United States Coast Guard vs. Captain Mark Stinziano

After Melogy publicly released his labor complaint against Maersk in June of 2019, the document found its way to Captain Jennifer Beck Williams, USCG. Williams was a 1990 graduate of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA), a prominent alumnus and booster of the USMMA, and a high ranking Coast Guard officer with a complicated history on the issue of maritime sexual misconduct.

In June of 2019 Williams was nearing retirement from the Coast Guard, but happened to be leading the division within the Coast Guard responsible for Suspension & Revocation investigations of the more than 200,000 American mariners who held credentials issued by the Coast Guard. Williams forwarded Melogy’s labor complaint to the CGIS, and opened a criminal investigation into Stinziano.

Shortly after the criminal investigation was opened by Captain Jennifer Beck Williams, Melogy was participating in a videotaped interview with criminal investigators from the CGIS regarding the report he had given to Maersk regarding Stinziano in 2015. According to Melogy, for more than 2 hours he told the CGIS investigators what had happened aboard the Maersk Idaho in late 2014 and early 2015, told the special agents about his many attempts to report Stinziano, told the investigators about the reporting requirements of 46 USC 10104 (Melogy says the investigators were not aware of the reporting requirement and court documents confirm they were not aware of the reporting requirement’s existence), and provided documents to investigators. After that interview with CGIS, Melogy believed the Coast Guard would finally take appropriate action to investigate Stinziano and hold him accountable.

But then a year passed with no action. By June of 2020 (a year after he sat for the CGIS interview) Melogy says it became clear to him that the Coast Guard was not going to take any action against Stinziano’s merchant mariner license. Melogy says he believes the Coast Guard’s plan all along had been to indefinitely delay taking any action on the case and to wait for Melogy to give up and go away.

But he didn’t give up. From June of 2019 when he sat for the CGIS interview, through June of 2020, Melogy investigated the Coast Guard in an effort to put pressure on the Coast Guard to bring a Suspension & Revocation (S&R) action against Stinziano’s merchant mariner’s license, and to expose the truth about the Coast Guard’s policies of intentionally ignoring the at-sea sexual abuse of merchant mariners.

Melogy began his investigation by looking at the Coast Guard’s current and historical record of enforcing the shipboard sexual abuse reporting requirement of 46 USC 10104, as well as the agency’s record of punishing merchant mariners via its Suspension & Revocation (S&R) administrative law process.

U.S. Coast Guard Suspension and Revocation (S&R) hearings are administrative proceedings before an U.S. Coast Guard Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) concerning a USCG-credentialed mariner’s right to hold a Merchant Mariner Credential (MMC) and the right to serve under the credential. Like truck drivers and airline pilots, the people who drive and operate ships must possess government-issued credentials and pass exams to obtain those credentials. For American mariners, the Coast Guard is the federal agency that issues those credentials.

The most severe punishment available in a Coast Guard S&R proceeding is the permanent revocation of a mariner’s credential(s), resulting in the mariner no longer being able to continue their career aboard vessels in the U.S. maritime industry. There is no criminal aspect to a S&R proceeding, nor are jail sentences or criminal fines imposed.

Melogy says he was shocked by what he discovered after investigating the Coast Guard’s record of using the S&R process to punish mariners for sexual misconduct. There was almost nothing to discover. According to the Coast Guard, there were more than 200,000 American merchant mariners who held credentials issued by the Coast Guard, and yet there was no publicly available evidence that the Coast Guard had ever punished any merchant mariners for sexual misconduct committed in the maritime industry.

There was also zero publicly available evidence that the U.S. Department of Justice had ever criminally prosecuted a merchant mariner for shipboard sexual misconduct. There was simply nothing in the public domain.

“How was that even possible?” Melogy wondered. “How was it possible that in the year 2020 there was zero publicly available information about anyone being investigated or punished for shipboard sexual misconduct in the history of the U.S. maritime industry?”

Combined with his own experience with the Coast Guard’s Stinziano investigation (which Melogy calls “frustrating, exasperating, and profoundly traumatizing”), the complete lack of publicly available information on the Coast Guard’s record of punishing maritime sexual predators looked to Melogy like a “decades-long, top down, agency-wide, pervasive effort by the U.S. Coast Guard to conceal from Congress, the public, and the maritime community the agency’s actual record on enforcing laws against sexual misconduct in the U.S. maritime industry.”

To Melogy, the Coast Guard’s policies on maritime abuse looked like a huge scandal hiding in plain sight. As Melogy continued to probe this riddle, he came to believe it was critical to the Coast Guard’s longstanding, unspoken policies on merchant mariner abuse that nothing ever became public. If any Coast Guard S&R case involving merchant mariner sexual misconduct became public, it would lead people to ask questions about how many other cases existed, and worse, it might catch the attention of Congress.

To Melogy, the Coast Guard’s policy of deliberately ignoring merchant mariner abuse and intentionally refusing to enforce laws and regulations against sexual misconduct at sea relied upon allowing the public and the maritime community to assume the Coast Guard punished sexual predators. Many people in the maritime community did incorrectly make that assumption.

The more digging Melogy did, the more he came to believe the Coast Guard saw the Stinziano case as simply one more merchant mariner sexual misconduct case the agency would bury and keep out of the public eye. By June of 2020–a year after his CGIS interview–Melogy says he had completely lost faith that the Coast Guard would take appropriate action in the Stinziano case.

Melogy thought that media coverage of the case and the investigation would help to put pressure on the Coast Guard, but despite extensive efforts to generate media interest in his investigation, Melogy was unsuccessful at finding serious interest from any journalists. Eventually, he decided he would have to become a journalist, and he would have to write, publish and distribute his own work about the case.

Needing proof of the agency’s policies, he turned to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Melogy says he didn’t want to simply submit a FOIA request to the Coast Guard and allow the agency to stall indefinitely on releasing records. Instead, he sought to turn the Stinziano case and his efforts to see justice served into a public fight with the Coast Guard, which might eventually gain the attention of Congress.

To become a journalist, he needed a platform. On the night of June 23, 2020 Melogy launched the Maritime Legal Aid & Advocacy website and began working on his first blog post, which he would publish on June 30, 2020. The title of that first blog post was, “An Epic Sexual Assault Scandal, 30 Years in the Making, is Coming for the U.S. Coast Guard. This FOIA Request is Only the Beginning.”

Melogy also created an Instagram account for MLAA and began publishing information about the Stinziano case on Instagram. Very quickly, mariners began following the account. Then someone sent MLAA their own story of abuse and harassment they experienced at sea and told MLAA they could publish the story if they did so anonymously.

MLAA published that story, which led to more people sending in stories of maritime abuse and harassment. Melogy says the outpouring of stories that flooded the website and Instagram account in the summer of 2020 was “shocking and emotionally overwhelming.”

As Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken of CNN would later write of the origin of MLAA:

An academy graduate and merchant mariner himself, 39-year-old Ryan Melogy never imagined he would become a one-man watchdog for the maritime industry. But that’s what happened. From his studio apartment in Los Angeles and even while working on a ship, he has spent the past two years battling the federal government for information about sexual misconduct at sea. As he posted updates, memes and criticism of the academy and the Coast Guard on social media and his blog, he gained a following and began hearing from mariners all around the world. Some blasted him for scaring women away from the industry, while others rallied behind his mission.

Suddenly, in the summer of 2020, Melogy had become the accidental leader of an amorphous and nascent movement against maritime harassment and abuse that he had somewhat accidentally started. In a short period of time, with the help of a few key volunteers, MLAA published dozens of first person accounts of maritime sexual harassment and assault that were submitted to MLAA by survivors. Melogy was also contacted by others who had either experienced or witnessed Captain Stinziano’s pattern of sexual misconduct at sea, and from these whistleblowers Melogy obtained critical evidence against Stinziano that he would eventually give to the Coast Guard.

The evidence against Stinziano that Melogy obtained in the summer of 2020 forced the Coast Guard’s hand, and on August 20, 2020 Commandant Karl Schultz ordered Suspension & Revocation charges be brought against Stinziano’s merchant mariner’s license. Eventually, the Coast Guard would amend its S&R Complaint against Stinziano to add additional charges related to sexual misconduct he directed at a 2nd USMMA cadet aboard the M/V Maersk Idaho.

USCG vs. Stinziano would become the first public sexual misconduct S&R case brought against a USCG-credentialed mariner in at least a generation, and the decision to charge Stinziano represented a major policy shift by the Coast Guard. It was a policy change that was approved by Coast Guard Commandant Karl Schultz. Melogy says that in the summer of 2020, as the Coast Guard was seriously weighing S&R charges against Stinziano, one Coast Guard investigator even told him, “this is on the Commandant’s desk.”

As the Stinziano S&R case was awaiting trial in early 2021, Commandant Karl Schultz was still leading the Coast Guard, and Schultz was still sitting on the explosive Operation Fouled Anchor Investigation Report. By that time, Melogy had forced the Coast Guard to turn over some records related to their merchant mariner sexual misconduct policies via FOIA, pursuant to the original FOIA Request slash blog post. MLAA subsequently published numerous stories from these documents, including:

All of the stories MLAA published were original reporting based on documents obtained from the Coast Guard via the FOIA. None of the stories had ever been reported or ever reached public awareness before MLAA pushed the issue into the consciousness of the maritime industry in 2020 and 2021.

MLAA’s articles did not paint a flattering picture of the Coast Guard, or the Coast Guard’s Administrative Law Judge Court. In fact, these records were so sensitive to the ALJ Court that the Coast Guard redacted the names of the ALJ Judges who had signed secret settlement agreements with sexually predator mariners from the records they released to MLAA.

There was no legal basis in the FOIA to redact the names of federal judges, which was an issue MLAA brought forward on appeal (See: MLAA Files Appeal Against U.S. Coast Guard Seeking Secret Shipboard Sexual Assault Settlement Agreements, the Names of the Perpetrators, and the Names of Federal Judges Who Approved the Agreements).

In June of 2021 the S&R trial for Stinziano was held in Baltimore with Michael Devine presiding. Devine was a Coast Guard lifer. A 1975 graduate of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy (CGA), Devine attended the USCGA before women were allowed to matriculate. 50 years after he first joined the Coast Guard, Devine was still working for the Coast Guard and had been hand-selected by the Coast Guard leadership to preside over perhaps the most high profile and consequential S&R case in the agency’s history.

The selection of Devine to handle the Stinziano case occurred in the midst of MLAA publishing widely-circulated stories about the Court’s record of handing out what Melogy said were “slaps on the wrist to sex predator mariners” via secret deals that were unknown to Congress or to anyone outside of the Coast Guard other than the predators and their lawyers. The secret ALJ deals, approved by Coast Guard judges, were critical to the Coast Guard’s policies of preventing any mention of their merchant mariner sexual abuse enforcement efforts from reaching the public view.

Melogy’s and MLAA’s public criticisms of the Coast Guard ALJ Court were not the first to be made about the Court. The Coast Guard’s ALJ Court had a long history of corruption allegations leveled against it. Walter Brudzinski, the Chief Judge of the Coast Guard’s ALJ Court, had even been denied a federal judgeship in Virginia over corruption allegations from his time on the ALJ Court.

At least two former USCG ALJ judges left the Court and subsequently became Coast Guard ALJ court whistleblowers. Both whistleblower-judges were women, and both said that the primary mission of the USCG-ALJ court was to protect the Coast Guard. The corruption allegations of the ALJ whistleblowers included one judge’s assertion that the Chief Judge of the ALJ court referred to the Coast Guard (including its Administrative Law Court) as “one big happy family,” and in a sworn affidavit said she was pressured to “always rule in favor of the Coast Guard.”

See:

In 2008 the U.S. House of Representatives had even voted to “dismantle the Coast Guard’s administrative law system, stripping the service of its judicial role in prosecuting misconduct and negligence charges against civilian mariners in response to claims of bias in the Baltimore-based courts.” The effort was never adopted by the Senate, however, and the Court continued on the same path.

Months before they broke the Operation Fouled Anchor scandal, CNN’s Hicken and Ellis reported on the corruption allegations within the Coast Guard ALJ Court. On March 16, 2023 CNN published a bombshell investigative piece that included quotes from an interview Hicken and Ellis conducted with former Coast Guard Judge Jeffie Massey. Massey told Hicken and Ellis the Coast Guard ALJ Court had a “culture of misogyny” and that “all the boys were running the show.”

Judge Massey also told CNN that during her time as a judge on the Coast Guard Court, Massey witnessed the “rabid” way the Coast Guard's judges went after even minor drug offenses, but said that “sex crimes were not recognized as a serious issue” by the Coast Guard or its ALJ Court. Judge Massey also told CNN that a “cultural transformation” at the Coast Guard was long overdue.

According to Melogy, there was little danger that Judge Michael Devine would turn whistleblower or deviate from the Commandant’s script for his ALJ Court in the Stinziano case. According to Melogy, with his impeccable Coast Guard pedigree, Devine could be counted on by Commandant Karl Schultz and by Walter Brudzinski (the Coast Guard’s Chief ALJ) to protect the Coast Guard’s interests in USCG vs. Stinziano.

Judge Brudzinski (CG-00J) would have had a difficult time doing anything other than following the Commandant’s orders, given he occupied an office near the Commandant’s own office at Coast Guard Headquarters in Washington, D.C., was a member of the Coast Guard’s leadership team, and reported directly to the Commandant according to a “macro organization chart of the U.S. Coast Guard.”

In the highly unusual and possibly unique structure of the U.S. Coast Guard, the Commandant exerted ultimate authority over the criminal investigators, the S&R investigators, the S&R prosecutors (and thus the power of ultimate prosecutorial discretion), and the Chief Administrative Law Judge who would adjudicate S&R cases. Finally, the Commandant possessed the power to overturn any decision of the Coast Guard’s ALJ Court by exercising appellate power as the “supreme court” of the S&R system. In the words of one of the whistleblower ALJ’s, by all appearances the Coast Guard’s S&R system was—and remains, “one big happy family.”

In June of 2021—during COVID, and 6 ½ years after he first submitted his written report about Stinziano to Maersk—a Suspension & Revocation trial was finally held in Baltimore in the case of USCG vs. Captain Mark Stinziano. According to Melogy, Judge Devine placed the defense table directly in front of the witness stand in the small courtroom, which meant that witnesses testifying against Stinziano were required to sit directly in front of Captain Stinziano at a distance of about 6 feet.

Over the course of two days, Melogy testified against Captain Stinziano. According to the transcript of the hearing, Stinziano’s defense attorney aggressively attacked Melogy in an attempt to discredit him. According to Tradewinds, Stinziano’s defense attorney William Hewig III “painted Melogy as a poor mariner, who made several mistakes on the voyage and held a vendetta against Stinziano for giving him a bad evaluation.”

Two former USMMA cadets who alleged they had been subjected to sexual misconduct and abuse by Stinziano also testified against him. According to documents obtained and reviewed by Tradewinds:

“Stinziano was accused of a litany of inappropriate acts, primarily targeting a deck cadet while he was chief mate of the US-flagged Maersk Idaho…Stinziano was accused of groping the cadet multiple times over the course of the voyage…He also allegedly grabbed the cadet from behind and pressed his groin against him and simulated sex during a lifeboat drill. During the trial, the cadet said Stinziano did it a second time while he was at the chart table…Stinziano is further accused of raising his fist in a threat to punch the cadet in the groin, drawing a penis on his hard hat during work with shipmates and requiring the cadet to refer to the chief mate as “big daddy” and to refer to himself as “buttercup”.

The testimony offered by former cadets who Stinziano subjected to assaults and pervasive and humiliating sexual degradation aboard the Maersk Idaho was incredibly disturbing. Coast Guard Judge Michael Devine listened to all of it. The Report Melogy submitted to Maersk and Captain Willers aboard the Maersk Idaho, as well as the labor complaint Melogy filed against Maersk were entered into evidence by the prosecution, and also read by Devine.

In that complaint Melogy wrote:

“On the bridge, at sea, I saw the Chief Mate approach the Deck Cadet from behind, grab him and simulate ‘humping’ or anal sex on the cadet’s backside…Stinziano is a short, stocky, and strong man. What I saw was Stinziano approach the Deck Cadet from behind, and without warning, wrap his powerful arms around the Deck Cadet’s arms and around the Cadet’s body, and then proceed to repeatedly and forcefully grind his own genitals into the Deck Cadet’s buttocks, simulating anal sex. Stinziano laughed throughout the attack, and the Deck Cadet was powerless to remove himself from Stinziano’s grasp….”

At the hearing, the victim of that assault was asked about the repeated gropings of his genitals and repeated sexual assaults Stinziano directed at him, and he was asked whether or not he thought it was funny:

Prosecutor: Was there some indication from Chief Mate Stinziano that he intended [the sexual assaults] as a joke or he wanted you to think that it was a joke?

Cadet: I'm not quite sure what his intentions for me were. But I didn't consider it very funny.

Prosecutor: So was it a joke to you?

Cadet: No.

At Stinziano’s trial, the former USMMA Deck Cadet also testified that Stinziano made him watch a movie where a baby was raped. This testimony was corroborated by a 2nd former USMMA cadet who testified that Stinziano had also forced him to watch the same movie aboard the M/V Maersk Idaho:

Prosecutor: Ok, were there any situations involving movies?

Cadet: Sometimes we would go to his room to watch movies and there was one movie…I can’t remember the title of the film but it involved I believe cutting a baby out of a woman and then the baby was raped, that’s what I remember from the film.

Prosecutor: And do you remember anything else about that film?

Cadet: I think it started out as a sort of normal film, and then turned into this scene, it was pretty graphic of the woman getting cut open and the baby being raped.

The former USMMA deck cadet also testified to the abusive and illegal working conditions that Stinziano forced upon the cadets. In his original report to Maersk, Melogy had complained to Maersk about Stinziano’s treatment of the Deck Cadet aboard the M/V Maersk Idaho. In that Report to Maersk, Melogy wrote:

“I attended the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, sailed for 1 year as a cadet aboard various ships and know hundreds of other USMMA graduates who have sailed as cadets. I have never seen or heard of a cadet being treated as unacceptably and abusively as the deck cadet has been treated aboard the Maersk Idaho…[the] Cadet has been made to work in excess of 16 hours in a 24 hour period on numerous occasions, and on several occasions has worked more than 20 hours in 24 hour periods. I have seen him dizzy with exhaustion on several occasions when he was required by the Chief Mate [Stinziano] to work many more hours than even I was working. I believe that the Deck Cadet was frequently required to work more hours than any other crew member on the ship, with the possible exception of the Chief Mate himself. He has not been given enough time to complete his sea projects, he has not been given set working hours, his time has not been respected, and he has been treated as the personal property of the Chief Mate, on call to do anything the Chief Mate wants him to do at any time. On top of this abusive work load, [the] Cadet has been sexually harassed, intimidated, and in cases suffered from conduct that could be considered sexual abuse at the hands of the Chief Mate. I found the Chief Mate’s treatment of [the Deck] Cadet and at times the Engine Cadet to be nauseating — sickening.”

At Stinziano’s trial, with Captain Stinziano sitting 6 feet in front of him at the defense table, the former Deck Cadet testified to the brutal working conditions that Melogy had witnessed and reported to Maersk:

Prosecutor: Okay, do you – what was your working environment, as far as how—if I may rephrase. You testified Chief Mate Stinziano was in charge of your hours and setting how, what type of work you did on the Idaho. What was that environment like with that?

Cadet: At times the work hours could be rather egregious, I would say. On several occasions he had me working for over 24 hours. There was one occasion I remember, I believe there was a valve broken in the bow of the vessel, and I can’t remember exactly what we were doing. But we had been working on it, it had been like fifteen hours and we, and I requested some lunch. Chief Mate responded that he hasn’t eaten lunch yet, we shouldn’t have lunch. Eventually we were granted like ten minutes to eat and then we had to go back to work.

Prosecutor: And how, how did that make you feel?

Cadet: It didn’t make me feel great about myself. I felt I had been working rather hard. I just wanted to eat something before we got back to work.

The former Deck Cadet was then asked to testify as to how this abusive shipboard treatment from Stinziano made him feel, and about the impact it had on his life and on his career. The former Cadet testified that Stinziano’s abuse led to depression, a desire to quit the Merchant Marine Academy, and ultimately derailed his plan to work at sea upon graduation:

Cadet: At the time, I had kind of suppressed the reaction to everything so that I didn’t think of it as a huge deal. But as I, as it went on, the effect of it was kind of wearing on me. It was just, I don’t know, it was an odd feeling, it just made me feel like less of a person I would say, the treatment I received on the vessel. And I just felt it was pretty tough, I didn’t want other cadets to experience it.

Prosecutor: And the treatment, when you say, “The treatment you received,” the treatment from Chief Mate Stinziano?

Cadet: Yup.

Prosector: Okay, And when you talk about how it made you feel like less of a person, how else has it affected you in your daily life after the Maersk Idaho?

Cadet: When I left the vessel I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue with that career path. I was pretty sure I wanted to leave the school, because it made me feel like I wasn’t strong enough, I guess, for the industry. Because I had assumed that was kind of how all vessels operated. So I felt like maybe I wasn’t cut out for it. So I just didn’t like the way it felt. I was pretty worn out, depressed, so I considered dropping out of school but I didn’t, I don’t know why I didn’t, but I didn’t.

The former USMMA Deck Cadet also testified that Stinziano made the Cadet watch as Stinziano placed a pen into his own buttocks on the bridge of the M/V Maersk Idaho, and then made the Cadet smell the pen. Melogy also wrote about this incident in his labor complaint against Maersk:

Prosecutor: Okay, do you remember a situation that occurred on the vessel that involved any kind of pen, or writing instruments?

Cadet: Yes. There was an instance where someone was chewing pens on the bridge of the vessel. The chief mate [Stinziano] was upset that somebody was chewing pens on the bridge of the vessel so he wanted to teach them a lesson. So he unzipped his coveralls, rubbed the pen in his buttocks region so it would smell like his buttocks. And then he asked me to smell the pen to confirm it rubbed on his buttocks region and that way the suspect chewing the pens would at one point chew on the pen that smelled like his buttocks.

Prosecutor: So are you testifying that he physically, was there any physical contact, or did just get close to your person with this pen?

Cadet: He reached his arm out and presented it…he wanted it to be clear that the pen was being inserted into his buttocks.

After the S&R hearing was over, Melogy began to endure what he calls a “a long, painful period of waiting.” Melogy describes this period of time in mid 2021 as “a trough of troughs.” Of that period of his life Melogy said,

“The abuse and torture I had endured at sea, the retaliation I had experienced, the massive amounts of secondary trauma I had absorbed from the more than 100 victims of maritime abuse I had worked with, counseled, or communicated with through MLAA, the online hate and threats directed at me, and a years-long fight against some of the most powerful institutions and organizations in the country had taken a devastating toll on me. My mental health was in tatters, my physical health was seriously compromised, and my career in the maritime industry was finished. I'd been working at sea making a living for over five years, but given my profile as an activist no one would hire me to work at sea. I was broke, didn’t have a job or a career, was living in a van, didn’t have health insurance, and I was dealing with very serious PTSD but could not figure out how to turn things around. The path forward was totally unclear, and things were very, very dark in general. I really did not know how I would ever get my life back on track. When I look back on that period of time I think I was not very far away from death.”

And right then, in September of 2021, when things were at their absolute darkest for him, something miraculous happened that changed everything for Melogy.

Midshipman-X

The submissions to MLAA’s rudimentary whistleblower platform were unpredictable, nearly impossible to solicit, and tended to come in waves, Melogy said. It was like a flywheel where stories inspired others to share their stories, but how to start the flywheel was a mystery. By August of 2021 MLAA had not received any submissions for months, although there were several whistleblowers with final drafts of their accounts who were on the fence about whether or not to come forward. Melogy says that of the more than 50 accounts published by MLAA, there were at least 50 more mariners or former mariners who Melogy and other volunteers worked with to develop their first person narratives. But at the end of the process, at least half would change their mind and decide not to move forward with publishing their stories.

Then, in August of 2021 a survivor of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy’s Sea Year program who had been on the fence for months finally gave MLAA permission to publish a first person account of their Sea Year experience. In accordance with MLAA’s provocative, in-your-face style guide, that account was given the title, I was Sexually Assaulted During Sea Year: Afterwards, My ATR Threatened to “Stick” Me, Never Asked Me Questions, Reported It, or Investigated. Then He Sent Another Cadet to the Same Ship Days Later.

Shortly afterwards, MLAA was contacted by Don Burnham, a 1956 graduate of the USMMA. Don shared his own story of shipboard sexual abuse from his time as a cadet in the 1950s and allowed MLAA to publish his story, which became U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Class of 1956 Graduate Recounts Being Assigned to a Ship with a Sexually Predatory Captain During Sea Year in 1954.

A Midshipman at the USMMA who had been following the MLAA Instagram account read both of those stories, which inspired her to contact MLAA with her own story. She told MLAA that its posts had helped her process her own trauma, and she wanted to help others. Her name was Hope Hicks and she was a member of the USMMA class of 2022. When Hicks contacted MLAA, she was a student at the USMMA and had recently begun her senior year.

As Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken of CNN would later write of Hope’s decision to contact MLAA:

Then, one day in early September last year, he [Melogy] received a message from a current student at the US Merchant Marine Academy. The woman wrote, in painstaking detail, how she was repeatedly sexually harassed and eventually raped at sea by her boss in 2019 when she was 19 years old. She described waking up to find blood on her sheets after being pressured to take repeated shots of alcohol the previous night, and said that since returning to campus, she learned of nine other female students at the academy who said they had also been raped during their Sea Year. At the end of her message to Melogy she wrote, “You can publish this.” Under the pseudonym “Midshipman-X,” Melogy posted the woman’s account, which would go on to spark the current reckoning inside the academy and industry.

Prior to publishing Hicks’ story, MLAA had published dozens of similar whistleblower accounts of maritime harassment and abuse. Accounts published by MLAA had previously led to major changes at Maine Maritime Academy, including the resignation of Maine Maritime Academy’s President. And in its short life, MLAA had been no stranger to controversy or attention from the maritime industry. But Hope’s story would hit completely differently than anything MLAA had previously published.

According to Melogy, the process of editing and finalizing Hicks’ initial account for publication involved several long and in-depth interviews and a collaborative process of revising and editing her account that was difficult for both of them. Melogy says that reading Hope’s final draft all at once left him in tears, emotionally devastated, physically nauseous, and deeply angry.

Before he published her story, Melogy says he had a very frank conversation with Midshipman Hicks about the potential ramifications of what she was doing by blowing the whistle. Melogy says he told Hicks that even though they were publishing her story pseudonymously as “Midshipman-X,” there was a significant risk that she would be identified through the many details she had chosen to include in her story. According to Melogy, he warned Hicks that her story was explosive and would likely reach a wide audience, and he offered her a sincere off-ramp.

“You don’t have to go through with this,” Melogy says he told her. “We can wait until you graduate to publish this.”

“I don’t want to wait,” Melogy says Hicks responded. “I want to set off a bomb.”

According to Melogy, he then told Hicks that if she wanted to set off a bomb, she had come to the right place. Melogy and MLAA published Hope’s story on September 28, 2021. Within a week of publishing her story, both of their lives had completely changed—forever.

After simmering for a few days, the story’s first major breakthrough happened on October 2, 2021 when acting Administrator of the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) Lucinda Lessley and U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) #2 Polly Trottenberg published a public memo of support for Midshipman-X.

In their Midshipman-X Memo, Lessley and Trottenbergy both pledged their “unwavering support for the individual who has shared her story of a sexual assault that took place during Sea Year,” and wrote they “stand ready to provide our support to her and to all survivors.” After an extensive search, the October 2, 2021 memo appears to be the first and last time anyone employed by the USMMA, MARAD or the USDOT ever publicly used the word “survivor” in the context of the USMMA, its Sea Year program, or sex crimes committed against their students.

Melogy had been shouting about the ongoing, unpunished sex crime epidemic affecting participants in the USMMA’s Sea Year program, had been publishing the stories of survivors, and had been trying to gain the attention of journalists and government leaders for years—but to no avail. Midshipman-X changed all of that nearly overnight. After the October 2, 2021 memo was released by MARAD and the USDOT, the media floodgates opened, and Melogy was contacted by journalists from all over the world who wanted to talk to him about Midshipman-X and about the broader problems in the maritime industry that had allowed this heinous crime to be perpetrated against this courageous young woman.

On October 10, 2021 influential maritime journalist and gCaptain founder John Konrad published a powerful essay about the case he titled, “Rape At Sea – An Open Letter To Midshipman X.” Konrad’s essay, which has been read more than 30,000 times, helped propel Hicks’ story across the global maritime industry and into the halls of Congress.

In his open letter to Hope Hicks, Konrad wrote,

I do not know your name — but your words are forever seared on my soul. Words that should be required reading for men and women of all ages and at all levels in our industry.

Words that made me cry. Words that took courage to share. Words I wish you never had to write. Words I pray my daughter never does…

I do not know your name Midshipman-X — but I know many women who have shared horrific at sea accounts with us.

You were failed by a mariner culture that has gone on for year after year after year for centuries. Centuries of rape – first of men, now of men and women – at sea. A culture that promotes passivity. A culture that is not understood and mostly ignored by our society. A culture encourages seafarers to simply turn a blind eye.

It’s obscene, and it’s a failure that lies at all our feet. We mariners have much to be proud of but not this. Never this…

On October 12, 2021, Senator Maria Cantwell (D-WA), in her capacity as Chair of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, sent a letter to MARAD demanding a response related to information that has been posted on the MLAA website, including the Midshipman-X blog post. In her first public letter to MARAD, Senator Cantwell wrote:

“I write to express my grave concern over the allegations of rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment made by midshipmen at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and the response by you and others at the Department of Transportation (“DOT”). Through the Maritime Legal Aid & Advocacy (“MLAA”), a legal advocacy group formed on behalf of mariners, victims’ stories of shipboard sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape have bravely shared their personal stories in blog posts on the group’s website…The despicable accounts put forth by brave young women and men just starting promising careers in the maritime industry are frightening and unacceptable. Many of these allegations involve a repeated pattern of crimes and intimidations committed by people in positions of power and responsibility on merchant ships, and include alleged poor oversight or policy failures of USMMA officials and Coast Guard investigators.

MLAA had arrived in the halls of Congress, and real change was finally on the way.

On October 14, 2021, four days after Konrad published his piece, the Washington Post published a story about the case: “A Merchant Marine Academy Cadet Says She Was Raped at Sea. Her Story Has Washington Looking for Answers.”

This WaPo story featured the only interview Hope would give to the media during the period of time between when her story was first published on September 28, 2021 and when she went public with her identity in June of 2022 by filing a lawsuit against Maersk three days before her graduation from the USMMA.

WaPo’s October 14, 2021 story contained powerful quotes from Hope, including, “I believe the academy fails everyone,” the midshipman said. “They throw us out into a situation where we are the bottom of the bottom and we’re made to feel like it’s normal to be treated the way we are treated.”

Blake Ellis, Melanie Hicken, & CNN Enter the Fight

As the Midshipman-X story was breaking all over the world, Melogy was contacted by CNN reporters Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken who had been deeply moved by Hicks’ story and wanted to write about the case. On October 12, 2021, about two weeks after MLAA published Hope’s blog post, Ellis and Hicken published their first story on the Midshipman-X case: ‘I was trapped’: Shipping giant investigates alleged rape of 19-year-old during federal training program:

“She was sickened by the number of young women getting raped at sea,” said her attorney Ryan Melogy, founder of the nonprofit that published her story. “Nothing was being done about the problem. She wants to see real change and real accountability for what happened to her and far too many others.”

Denmark-based Maersk, which is the world’s largest container shipping company, said in a statement issued Friday…: “We are shocked and deeply saddened about what we have read. We take this situation seriously and are disturbed by the allegations made in this anonymous posting which has only recently been brought to our attention,” said Bill Woodhour, CEO of Maersk Line, Limited, the company’s US subsidiary. “We do everything we can to ensure that all of our workplace environments, including vessels, are a safe and welcoming workplace and we’ve launched a top to bottom investigation.”

Only weeks earlier, Maersk Line, Limited had filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Coast Guard in an effort to attack Melogy, defend Captain Mark Stinziano, and undermine the Coast Guard’s S&R prosecutors’ case against Stinziano. When Woodhour made comments to CNN for their October 12, 2021 story, Maersk was still employing Stinziano and still allowing him to supervise cadets aboard Maersk vessels, despite the Coast Guard’s pending sexual abuse case against him.

For Melogy, who had for years been a lone voice publicly shouting about the dark side of the maritime industry, the arrival of Blake Ellis, Melanie Hicken, and CNN to the cause felt like “a massive achievement,” of which Melogy said:

“One day I couldn't get anyone to listen to me, couldn’t get any journalists to cover anything I was writing about and exposing, and the next day two very accomplished investigative journalists from one of the world’s most recognized media brands wanted to dig in. It was a dream come true. And I could tell from our early conversations that Blake and Melanie really believed me when I explained that the Midshipman-X story was “tip of the iceberg” stuff, and that I could lay out an outline of the systemic failures for them, step by step–and that it all eventually led back to the U.S. Coast Guard, which was the only organization that had the power to change the industry. It was incredible to help them and then to watch their stories get published.”

When Hicken and Ellis of CNN dug into the Midshipman-X case, they already had a proven track record of exposing sexual abuse scandals via big investigative pieces. They had written about “Police officers convicted of rape, murder and other serious crimes who were collecting tens of millions of dollars during retirement, and produced the series “Sick, Dying and Raped in America's Nursing Homes.”

The duo had also covered “The secret world of government debt collection,” did award-winning reporting on Nuedexta, and published a book: A Deal with the Devil: The Dark and Twisted True Story of One of the Biggest Cons in History.

But getting to the bottom of the Midshipman-X case and the broader problem of sexual abuse in the maritime industry presented unique challenges. The maritime world was difficult to penetrate and it was very difficult to find victims and survivors willing to come forward to speak out. And there were layers of interconnected agencies and organizations that bore responsibility for what had happened to Midshipman Hicks and to many others at sea.

There was the shipping company Maersk, which was divided between its American subsidiary that operated the vessel as well as its global umbrella company in Denmark. At least three different maritime labor unions represented mariners involved in the incident, including the accused rapist. There were law firms and insurance companies behind the scenes. The U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA) operated and promoted the safety of the Sea Year program that had sent Hicks to the Maersk vessel where she was raped. The USMMA was operated by the U.S. Maritime Administration, with close supervision and involvement of the U.S. Department of Transportation led by Pete Buttigieg.

Then there was the U.S. Coast Guard, which issued merchant mariner credentials to Hicks and to every other mariner aboard her vessel, regulated and regularly inspected the safety of the vessel itself, was responsible for investigating criminal conduct aboard the vessel and referring the findings to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). The DOJ was responsible for criminally prosecuting mariners, but had never done so for a maritime sex crime aboard a commercial vessel in at least 30 years prior to the Midshipman-X case.

From the beginning of their relationship in October of 2021, Melogy says he urged Hicken and Ellis to write about the Coast Guard’s intentional failures to protect mariners at sea from sexual violence and misconduct. Hicken and Ellis wanted to do a big Coast Guard story, he says, but it would take the duo time to build up to such a complex and technical exposé.

As Melogy began sharing information and documents with Hicken and Ellis, the duo began doggedly reporting on the Midshipman-X case, related problems in the maritime industry, and the disaster at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy through old-school investigative journalism—quickly developing sources from all over the maritime industry, in Congress, and within the Coast Guard community.

On November 3, 2021, in a story titled, “Government suspends training at sea program after college student says she and others were raped,” the duo wrote:

The federal government’s academy for merchant mariners is halting a key training program that sends students thousands of miles away from campus on commercial ships after a 19-year-old student was allegedly raped at sea. The decision by the Department of Transportation, which oversees the US Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA), came just weeks before students were set to embark on their “Sea Year” voyage, in which students are typically sent in pairs to work alongside older, predominantly male crew members. In a letter to students notifying them that the program has been temporarily suspended, school and transportation officials said the academy and the maritime industry were confronting a “challenging time” and that the decision to halt the program was “one of the most difficult we have faced.” Just days earlier, congressional lawmakers expressed concern that students at the academy were being put in danger while participating in the Sea Year program.

On December 15, 2021, less than two months after they reported the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) was suspending the Sea Year program, Ellis and Hicken published a story about the USDOT restarting the troubled program. In “Government reforms training at sea program after alleged rape of 19-year-old student,” Ellis and Hicken wrote: “The federal government plans to begin sending students at the US Merchant Marine Academy back to sea later this month, resuming a key training program that had been temporarily suspended in the wake of an allegation that a 19-year-old student was raped on a ship.”

Ellis and Hicken then began working on a long, deeply-researched story about the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (USMMA). CNN published their story about the USMMA on February 2, 2022 under the title, “Culture of fear at Merchant Marine Academy silences students who say they were sexually harassed and assaulted.” In words that would sound very familiar to readers who would eventually read Ellis and Hicken’s reporting on the Coast Guard Academy’s Fouled Anchor scandal, the two journalists wrote:

“She and others in the school community told reporters that sexual assault and harassment are disturbingly common at the academy, but a culture of fear has silenced victims for years. They spoke out in the wake of an explosive account from a current student who wrote that she was raped at sea in 2019 by her supervisor. As her allegations spread throughout the maritime industry and federal government last fall, lawmakers slammed the academy for failing to keep students safe. Government officials then temporarily suspended Sea Year and rolled out new safety measures for ship operators and the academy.

“But this is not the first time the academy has promised to better protect students, and government data reveals how rarely alleged assailants have been held accountable both on campus and at sea, despite previous reforms. A CNN review of school policies, meanwhile, shows that victims still face significant barriers to reporting sexual assault and could jeopardize their education and careers by coming forward.”

Melogy agreed to participate in this story, along others in the USMMA community, including Denise Krepp, who Ellis and Hicken wrote, “was forced to resign [her] position as Maritime Administration Chief Counsel after reporting sexual assault at the US Merchant Marine Academy in 2011.” Hicken and Ellis were also able to convince Stephanie Vincent-Sheldon to participate in the story. A graduate of the USMMA, Vincent-Sheldon was “the only student at the academy known to have had a sexual assault case criminally prosecuted, and that was back in 1997, when she reported an older male student barged into her room and molested her in her bed.”

According to Vincent-Sheldon, USMMA officials “told her to keep what happened quiet…but she ignored this advice and went to local police, and her assailant was eventually found guilty and sentenced to prison.” Discussing the aftermath of reporting the crime, she told CNN “It’s basically a firing squad [at the Academy]…How many bullets are you going to take before you disenroll?”